Emily Dickinson – The Music of Poetry

As the Â鶹¹ÙÍøÊ×Ò³Èë¿Ú Symphony Orchestra performs Aaron Copland’s ‘Eight Poems of Emily Dickinson’, we look at how the reclusive American poet inspired countless composers, and pick five essential pieces of music she inspired

Passionate, astute, concentrated. The poems of Emily Dickinson (1830–86) have marked her out as one of the great American poets and she has been placed by the critic Harold Bloom as a key figure of Western literature alongside Shakespeare, Dickens and Jane Austen.

She wrote around 1,800 poems (though only 10 were published during her lifetime), which abound with lyricism, rhythmic vigour and rich imagery. They also make frequent reference to music and to the sounds around her, so it’s no surprise that many composers have been drawn to setting her poems to music.

It’s estimated that her poem ‘Musicians wrestle everywhere’ alone has been set by more than 275 composers.

But Dickinson remained shrouded by obscurity for most of her lifetime. She was born in the New England college town of Amherst in 1830, to Edward – an ambitious lawyer who later served a term in Congress – and Emily Dickinson.

Nature and the sciences fired Emily’s imagination as a student at Amherst College, after which she briefly attended the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. Despite the institution’s religious slant, Emily at the time remained defiantly questioning. A fellow student recalled an occasion when their teacher asked everyone who ‘wanted to be a Christian’ to stand. Emily remained seated. She explained: ‘They thought it queer I didn’t rise. I thought a lie would be queerer.’ A few years later she wrote a poem with the opening lines: ‘Some keep the Sabbath going to Church – / I keep it, staying at Home –.’

Returning home after completing her education, Emily resented the social visits she was expected to make as a member of a prominent family and became increasingly withdrawn. Most of her friendships were conducted by letter and she would often speak to visitors through a closed door. She left Amherst on only three occasions. For the last 20 years of her life she barely left her home. But it was perhaps only through her withdrawal from society that she was able to become such a sharp observer of it.

Dickinson was considered an eccentric locally, but the Amherst citizens would surely have been even more struck by her poems, which are littered with idiosyncratic capitalisation, dashes and apostrophes – idiosyncrasies that were at first ironed out by short-sighted if well-meaning editors.

Though she received encouragement from a small handful of acquaintances, it was only after her death – when her sister Lavinia found 40 hand-sewn manuscript books crammed with Emily’s writings – that her work reached the public. Her first volume of poems was published in 1890, four years after her death.

Literary critic Helen Vendler neatly summarises Dickinson’s endless variety and invention. ‘She is epigrammatic, terse, abrupt, surprising, unsettling, flirtatious, savage, winsome, metaphysical, provocative, blasphemous, tragic, funny – and the list of adjectives could be extended since we have almost 1,800 poems to draw on.’

Aaron Copland (1900–90)

Eight Songs of Emily Dickinson (1949–50, orch. 1958–70)

In 1949–50, Copland, known to many as the ‘Dean of American Music’, wrote 12 songs for voice and piano to poems by Dickinson, beginning with ‘Because I could not stop for Death’, which he placed last in the cycle.

The composer remembered, ‘The first lines absolutely threw me: “Because I could not stop for Death – / He kindly stopped for me – / The carriage held but just Ourselves – And Immortality.”’

While working on the songs, Copland visited Dickinson’s home in Amherst and stood by the small writing table in her bedroom, ‘to see what she saw out of that window’.

In 1958 Copland began to arrange the 12 songs for voice and orchestra, but he didn’t finish until 1970, and even then he completed only eight. He finished them in time for a performance on his 70th birthday.

John Adams (born 1947)

Harmonium (1981)

Adams’s ‘Harmonium’

from the First Night of the Proms 2017

Though an experimenter in her own way, Emily Dickinson could hardly have imagined the Minimalist sound-world of John Adams, which would arrive around 100 years after her death, even if Adams was born only 80 miles east of her birthplace.

Adams’s half-hour choral symphony Harmonium falls into three movements. The first is a setting of John Donne, but for the remaining movements Adams chose contrasting poems by Dickinson. The first of these is ‘Because I could not stop for Death –’, the one Copland set in the last of his Dickinson songs. In Adams’s version, the chorus is sustained and floating, aptly reflecting the poem’s voice from the grave. Then comes ‘Wild nights – Wild nights!’, whose exuberance Adams matches with a constellation of tuned percussion.

Judith Weir (born 1954)

Moon and Star (1995)

Currently Master of the Queen’s Music, Judith Weir has long been inspired by the sky, stars and planets. For this glinting commission for the Â鶹¹ÙÍøÊ×Ò³Èë¿Ú Proms in 1995 – scored, like Adams’s Harmonium, for orchestra and chorus – she turned to Dickinson’s ‘Ah! Moon, – and Star!’.

For Weir, ‘Dickinson’s view of the vastness of space … seems, as her work so often does, startlingly modern. In expressing her idea that the universe is as large as we can imagine … she seems to be some years ahead of present-day thought on the subject.’

As in the middle movement of Harmonium, the voices are used for colouristic effect, rather than to realise the text – lending a suitably spacious and luminous effect.

Michael Tilson Thomas (born 1944)

Poems of Emily Dickinson (2002)

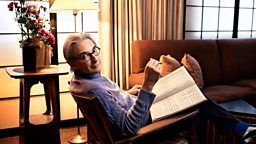

A star conductor who studied with the equally charismatic Leonard Bernstein, Michael Tilson Thomas – who recently relinquished his Music Directorship of the San Francisco Symphony after 25 years – is also a composer.

After a conversation with big-name soprano Renée Fleming in which they swapped favourite Dickinson poems, MTT (as he is affectionately known) began to get some musical ideas. Within less than two weeks he had composed three songs. Soon these grew to 10, seven of which he drew together in this song-cycle.

The San Francisco Chronicle critic at the 2002 premiere noted: ‘Thomas’s short settings bring out the distinctive flavour – at once self-confident and deceptively fluid – of these quintessentially American texts.’

Avoiding what he saw as the ‘touchy-feely’ poems that tend to attract composers, MTT was drawn to the ‘sardonic, bitter, quite cutting observations in her poetry. I wanted to focus on more of that aspect of her work, on its ironic quality, on its social criticism – and also on the sense of appreciation for just being alive, which is so much a part of her work.’

Jane Ira Bloom (born 1955)

Wild Lines: Improvising Emily Dickinson (2017)

Boston-born Jazz soprano saxophonist Jane Ira Bloom – like Dickinson and Adams, another Massachusettsan – released her double album inspired by Dickinson in 2017. The title, Wild Lines, is a play on Dickinson’s ‘Wild nights – Wild nights!’ (the poem with which Adams concluded his Harmonium). Adding a piano to her standard trio of sax, bass and drums, Bloom introduces the voice of actress Deborah Rush to bring to life the poems that inspired the musical items.

Bloom – who, like Copland, also visited Dickinson’s home and peered out of her bedroom window – was inspired to write the album when she heard that Dickinson had been a pianist and improviser. (The poet’s cousin John Graves described her late-night improvisations as ‘heavenly music’.)

For Bloom, there was a jazz-like quality to the poems: ‘I didn't always understand her but I always felt Emily’s use of words mirrored the way a jazz musician uses notes.’