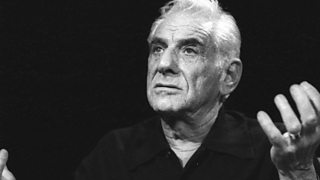

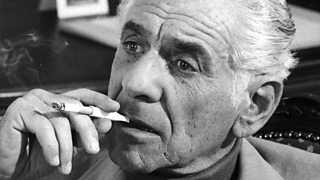

Why did the US government spy on Leonard Bernstein for 30 years?

For more than three decades the US government compiled covert reports on the political activities and associations of legendary conductor composer, Leonard Bernstein.

With claims of connections to communists, the Black Panthers and radicals, concerns about Bernstein's politics had reached the White House and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The golden boy of classical music – with a string of Broadway hits – had been blacklisted by the FBI.

Radio 3's The Bernstein Files opens secret FBI files on Leonard Bernstein and asks why the US Government spied him for more than three decades.

Photos © 麻豆官网首页入口

Legendary composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein was revered the world over for his talent; his work with the New York Philharmonic and his Broadway smash hit musical West Side Story are among his most celebrated accomplishments. Bernstein was also known as an engaged humanitarian who took an interest in civil rights and the anti-Vietnam War movement, among other causes. “My dad’s politics rose from his heart,” explains his daughter Jamie: “When he saw injustice he had to address it, he couldn’t just sit idle.”

Committed though he was, those that knew him would never have considered Bernstein an enemy of the state. However, as recently released files show, J Edgar Hoover’s FBI thought very differently. They spied on Bernstein for over 30 years, believing him to be a communist and a threat to national security.

But what exactly was it about classical music’s poster boy that had them so rattled?

Alma matters

It was raw musical talent that allowed the young Bernstein to progress from his humble family background to Harvard to study music. While there, he briefly associated with various organisations such as the American Soviet Music Society. He also attended a dinner organised by American Youth for Democracy, the youth wing of the Communist Party USA, and was rumoured to be a leading light in the John Reed society, a group founded in memory of the journalist and author of Ten Days That Shook The World, an account of the 1917 October Revolution.

Another flag for the FBI was Bernstein’s staging of pro-union opera The Cradle Will Rock by left-wing composer, lyricist and librettist Marc Blitzstein. However, Shirley Pearl, a friend of Bernstein’s at Harvard, saw nothing of the insurrectionist in him. “If he was an active communist, I never knew anything about it and we were very, very close – we remained friends all his life. I never got the sense that he was anything more than a sentimental left-leaning liberal.”

Profile and profiling

Bernstein’s career flourished quickly after leaving Harvard. He became assistant conductor at the New York Philharmonic and was thrust into the limelight in November 1943 when he had to fill in for guest conductor Bruno Walter, who had fallen ill. The New York Times was tipped off about Bernstein’s debut and it became front page news.

As Bernstein’s profile grew, so inevitably did the number of people and organisations interested in him. His daughter Nina said: “My dad would just give his name to anybody. If it was lefty, he was ok with it. I’m guessing he was not inspecting all too carefully, he was just that kind of a guy.”

The FBI’s file grew accordingly and at a feverish time, with the House of Representatives' House UnAmerican Activities Committee focusing its attention on communists and their sympathisers. Bernstein knew a number of people who were called to testify at HUAC, but he was never called himself. Nevertheless, the FBI’s ongoing concern about Bernstein was enough to put President Truman off attending a concert at which Bernstein was performing.

That presidential snub came in 1949. A few years later, in 1953, the FBI went on the offensive by making allegations about Bernstein’s sympathies via an anti-communist newsletter. That same year Bernstein was denied a passport renewal, a decision only overturned by signing a contrite affidavit in which he denied any involvement with the Communist Party and disowned any subversive activities that may have been carried out by organisations he’d previously come into contact with.

Without a passport and the ability to go on tour, Bernstein’s career could have been ruined.

West Side Story to wartime activist

The late 1950s was a period of particular success for Bernstein. West Side Story premiered in 1957 and, in the same year, Bernstein became the musical director of the New York Philharmonic. He also enjoyed favour with the White House when, a decade after Truman’s snub, Bernstein joined President Eisenhower for a celebration to mark the construction of New York's Lincoln Center.

Nixon鈥檚 advisers were worried that Bernstein was going to unleash an embarrassing, anti-war "trap" for the President.

Though the FBI file was still being added to, the subsequent Kennedy years were a period of harmony between Bernstein’s politics and the government’s direction, to the extent that the Kennedys and the Bernsteins dined together in the White House family quarters.

Kennedy’s presidency came to an abrupt and shocking end with his assassination in 1963. A few years later, Jackie Kennedy asked Bernstein to write a Mass to mark the opening of the the John F. Kennedy Center for Performing Arts in Washington DC. Bernstein took his inspiration from the anti-Vietnam War protests, specifically from Daniel Berrigan, a catholic priest imprisoned for setting fire to draft papers. Bernstein visited Berrigan in prison a number of times, visits that inevitably piqued the interest of the FBI and the White House.

As recordings released years later show, Nixon’s advisers were worried that Bernstein was going to unleash an embarrassing, anti-war "trap" for the President. However, when "Mass" premiered in September of 1971, the piece was an exploration of personal faith rather than a work of insurrection.

A seditious soir茅e?

The high noon moment of tension between the FBI and Bernstein had arguably already happened before the Kennedy Center Mass was performed.

On 14 January 1970, Bernstein’s wife Felicia, also an anti-war and civil rights activist, hosted a fundraiser at the Bernstein family home on Park Avenue in aid of a group of Black Panther members imprisoned without trial on terrorism charges.

The mixing of high society and Black Panther members at the party was too much for FBI boss J. Edgar Hoover (who, according to historian Tim Wiener “loathed and feared the Panthers”) and so he sanctioned a letter-writing campaign against the Bernsteins. This led to a deluge of hate mail and even to demonstrations outside the Bernsteins’ home.

This was the high point of political antipathy against Leonard Bernstein. It would finally pass when Hoover died in 1972, ending a controversial era of paranoia, and when Nixon, and indeed the whole country, became embroiled in Watergate. There were bigger fish to fry, and Bernstein, while a towering figure in music, was surely a relative minnow when it came to security threats.

“My father was never a communist,” says his son Alexander. “I guess you could call him a social democrat or a democratic socialist, communism, no, and he was adamant about that. My father was a great patriot and loved his country enormously… to be hounded like that and made to look less than a real American is just horrific.”

-

![]()

The Bernstein Files

Investigative journalist Jonathan Coffey opens the secret FBI files on Leonard Bernstein and asks why the US Government spied on him for more than three decades.

Fascinating features from Radio 3

-

![]()

John Cage, Zen and Japan

How American experimental composer John Cage came to write his infamous silent 4鈥�33鈥�.

-

![]()

Gabriel Prokofiev 鈥� My Family and Russia

Composer Gabriel Prokofiev explores the shifting relationship between Russian music and the state across three generations.

-

![]()

Electronic India

Musician Paul Purgas investigates the lost history of India鈥檚 electronic avant-garde.

-

![]()

Jazz Japan

An exploration of the rich and surprising history of jazz in Japan.