Why does luxury provoke social and political discord in every age?

As much as the allure of luxury lives through centuries, our unease about splendour and splashing out doesn’t seem to abate.

Exclusive brands are aware of both aspects — especially in uncertain times. At the height of the pandemic, luxury conglomerate LVMH (Moët Hennessy – Louis Vuitton SE) re-purposed its factories to produce hand sanitiser, and went without the French state’s financial support for companies, which looked to be a PR problem for them. The Four Seasons hotel in New York housed healthcare workers.

In Radio 3's The Deluxe Edition, Seán Williams finds that although luxury is, by definition, unnecessary and not for everyone, its success is underpinned by impeccable presentation. That can rescue it from controversy, including in the age of Coronavirus.

Out to lunch

Venturing out to a restaurant this month, I chose from the Michelin Guide. Going for a meal, I reasoned, should be really worth the risk. But I also felt guilty about the unnecessary culinary pleasure, the expense compared to weekly supermarket shops, and how the anecdote might come across. Britain is in recession, after all.

Dr Seán Williams

Seán is Lecturer in German and European Cultural History at the University of Sheffield. He has BA (Congratulatory First), MSt (Distinction), and DPhil degrees from Oxford. He has also studied in the USA and Germany. Before coming to Sheffield as a Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow in 2015, he taught German and comparative literature at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

I am reassured by government and my impressionable conscience that spending — if you have the money — is apparently a social good again. What’s more, it was hardly the “Ritzkrieg”: when the decadent dined on in London’s grand hotels, as other city buildings crumbled during the Second World War.

Nor had I led my lockdown life away from the world in the style of the 19th century’s luxury-loving Ludwig II of Bavaria: listening to specially commissioned Wagner in solitary opulence, sitting in a theatre just for one, as fine wine and artistic ecstasy rushed to the head. No, this was just lunch out. Or a treat. Call the occasion a “little luxury”, and it sounds OK.

Recording The Deluxe Edition for Radio 3 last year, I riffed, ironically, on the vocabulary and tone of diamonds adverts. I declared that the 45 minutes were made to be “timeless”. Time and again, I discovered the enduring appeal of luxury. I heard that the high-end market can be immune to recessions, and now luxury has turned out to be pandemic-proof. Due to coronavirus, charters of private jets have soared; the super-rich have bought up not just any property — but islands in particular. Now I want to reflect more on the other side of the coin: not so much on why luxury never ceases to be in demand. Rather, what makes opulence, profligacy, luxury so problematic?

When luxury went mainstream

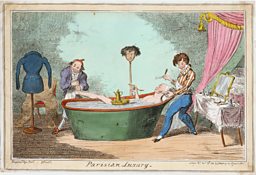

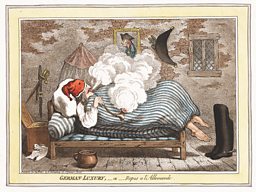

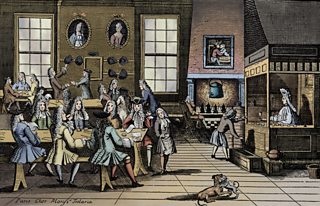

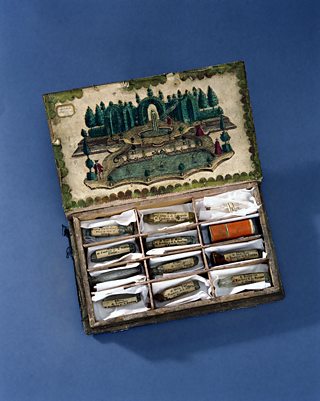

In Europe, luxury went mainstream in the 18th century. The middle classes embraced what had previously been the preserve of the aristocracy, in the main — or in praise of God. They justified the expense on account of luxury bringing them pleasure, convenience, and being good for the economy. Above all, luxury enabled self-expression. But loving the finer things in life too much could also be the downfall of an individual. Bach’s “Coffee Cantata” joked that women became coffee addicts; others feared financial ruin, or less interestingly: idleness. And if luxury helps you to express yourself, what if you style yourself as someone you’re not?

In 1700, average French servants spent ten per cent of their earnings on clothes. By 1780, they splurged around a third — despite the fact that their wages did not rise much. They actually bought little, investing instead in select, expensive items. This aroused suspicion from reactionaries, and pity from paternalist critics. Were servants a threat to an employer’s status, or in thrall to an oppressive way of life?

Norwegian-American theorist Thorstein Veblen was despondent that by the late 19th century, the proletarian revolution he hoped for would never materialise. He suspected the impoverished were too rapturous about mimicking high fashions from above. Whether the commonplace charges were aping the aristocracy, or a consumer not behaving like a proper woman (or if a man, too effeminately), people’s concerns could be well intentioned. But accusing luxury of corrupting individuals was also a covert way of trying to assert social control. Or an explicit assumption about what’s a real or “false need” for others.

The appeal of the exquisite

Another perceived problem of luxury in the past hinged on its 18th-century economic rationale: that any given society got richer if its attitude was liberal towards luxury. Sumptuous imports could also disadvantage the nation.

The appeal of the exquisite is often that it’s exotic, foreign. For territories without established trade routes, colonies, or global networks, luxury goods brought in from abroad were all the more expensive. The German King Frederick the Great tried to encourage substituting coffee with chicory, as a home-grown replacement. Two centuries later, the communist German Democratic Republic attempted something similar in the 1970s. In both cases, fake coffee fell foul of popular taste.

More dramatically, luxury is said to cause the collapse of civilisation. In The Deluxe Edition, I heard that it’s false to attribute the fall of the Roman Empire to excessive feasting and leadership blinded by bling. The same narrative has been spun — wrongly — for the fading of the Dutch Golden Age, or the revolutionary end to the French monarchy in 1789.

We might even apply it to our coronavirus era. In the salubrious suburbs of Connecticut, a soirée in March was reported to have been a “superspreader” event. Meanwhile in Europe, the Austrian Alps kept a lethal secret: skiing hotspots have been accused of hiding COVID-19 cases that returned with tourists to their home countries across the continent. Of course, Alpine resorts have long been associated with decadence, cosmopolitanism, and disease — thanks to fiction and film. The media stories of Austrian and US gatherings après ski or in high-end homes are in fact borne out by epidemiology, but they are also lacquered with the familiar cultural narrative: that luxury corrupts.

Universal opulence

The three problems of luxury that pop up across the centuries — that it’s said to harm the individual, the nation, or bastions of civilisation — are all from the perspective of consumers. Adam Smith imagined consumer society as “universal opulence.” But what of the producers? Another popular idea is that behind the luscious smells of an elusive perfume is a moral stench in its production. Think Patrick Süskind’s novel Perfume, made into a film — and also about the 18th century, by the way.

Most troublingly, exclusivity can be the effect of exploitation. The conditions for free workers are contested. In 1805, early socialist thinker Charles Hall objected that when the poor produced luxuries such as pottery or jewellery, they were robbed of valuable labour time that they could have spent tending their own land.

Today, luxury brands have caused outrage by moving production to factories in countries with much lower pay, and dubious employment practices. Though “necessities” may be exploitative also — and their story of creation spuriously justified. Cheaper products can be made in sweatshops, too. Indeed, at its best, luxury can privilege artisans over mass production. And some argue that in luxury services especially, staff tend to feel more pride and be particularly skilled in their work.

On a practical point, again in the 18th century, travelling salespeople preferred to carry luxury items because they were lighter — which is grist to the mill for those who claim that peddling luxury is more talk and performance than substance.

For luxuries made in slavery, there is no excuse. If being waited on hand and foot (rather inefficiently) is a sign of excess, these “servants” were in too many historical contexts themselves possessed goods.

And yet again in the 18th century, many luxury consumables, such as coffee, were produced in colonies. An age of free trade, at the expense of human freedom.

Certain luxury brands at that time traded on political counter-currents among consumers. There was a Wedgwood medallion worn by abolitionists, which depicted an enslaved black person. Its purpose and image are rightly questioned today: was it tokenism? A White Saviour narrative? The badge of protest is an early example of an expensive brand aligning itself with a political cause. Being worthy can add value.

Revelations of personal hypocrisy

The problems of luxury are not exclusive to luxury. But I think our reactions are all the more emphatic, in part because luxury is so appealing to many. This tension opens up the potential for revelations of personal hypocrisy. Enter the champagne socialist. Or the liberal who heralds luxury for growth, but imposes fixed ideas on what befits whom — and woe betide those who act above their station.

And what about that Rolex Republican running for office again, whose own name is both a luxury brand and a byword for populism? Luxury is illogical, its contractions reconcilable only in a false picture of a supposedly simpler past before modern capitalism, conjured up by nostalgia. Or in a future utopia in which everyone will share in plenty.

For the here and now, two things endure. Since the turning point in the 18th century, most of society hasn’t ceased to be uncomfortable about luxury in some way. And yet luxury’s lustre has longevity, too.

-

![]()

The Deluxe Edition

Dr Seán Williams takes a first class journey through the enduring contradictions of luxury, exploring its deep historical roots and its ever-present potential to provoke social and political discord.

Fascinating historical features from Radio 3

-

![]()

Of Dogs and Duchesses

Not just a lap warmer – explore the deep and meaningful relationship between small pooches and their 18th-century owners

-

![]()

16th-century tips for dancing with your cow

An old dairying manual reveals insights into our ancestors' relationships with livestock.

-

![]()

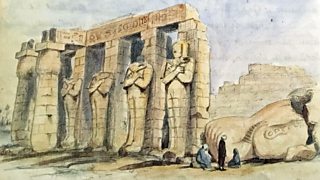

The Victorian Queens of Ancient Egypt

Samira Ahmed on the women who brought ancient Egypt to Britain’s industrial north.

-

![]()

Tudor Virtual Reality

Christina Faraday on the link between VR dinosaurs and a Tudor wall painting of the Judgement of Solomon.