Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage and Disappearing Queer Spaces

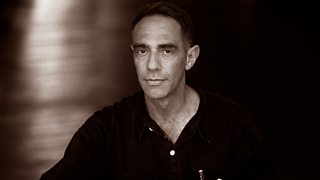

New Generation Thinker Diarmuid Hester reflects on saving Jarman’s house and garden.

From a distance, Prospect Cottage looks like many other fishermen’s cottages from the Victorian era that dot the coast of Britain. Up close, however, the small house and grounds around it show more evidence of upkeep than other examples might. It appears well kept, tidy even. Wind whistles between misshapen pieces of driftwood and curious geometric shapes in rusted iron, stood upright in the garden. Bushes with bright flowers in pinks and reds and whites burst forth from the shingle. The dark pitch of the cottage’s roof and walls set off the window and door frames lovely, painted the colour of sour-lemon-yellow.

I want to know how we do the history of spaces like these and if it’s possible to access the feel of a place.

The whole scene evokes especial care – acts reflected upon and deliberately made in undisturbed peace in one of Britain’s weirdest landscapes. Dungeness: a wide, inconceivably flat expanse under grey skies, presided over by a pair of nuclear power stations that emit an incessant hum.

Prospect Cottage was, of course, the home of Derek Jarman, the famous gay artist, activist, and filmmaker who purchased this shack on the Kent coast in 1983 and lived here for many of his remaining years. The house and its setting massively influenced his late style and inspired his cult films like The Last of England and The Garden, his journal Modern Nature, and various other artistic experiments including sculpture and gardening. The place was so important that even during Jarman’s lifetime it assumed a quasi-mythic status among his audiences – his queer fans in particular.

Since his death from AIDS-related complications in 1994, it has become a kind of secular shrine for LGBTQ people across the world. Many have made the pilgrimage here to pay their respects or experience for themselves the space where his powerful, poignant artworks were created.

In January of this year, following the death of Jarman’s partner, Prospect Cottage went up for sale. Reaction to the news was swift and the charity called Art Fund launched a crowdfunding campaign to raise the money needed to acquire the house and its grounds for public ownership. Backed by Jarman’s famous friends and fans, including Tilda Swinton, Tacita Dean, and Wolfgang Tillmans, by the beginning of April the campaign had succeeded in raising the necessary £3.5million, with 8000 individual donors pledging between £5 and £3000. Prospect Cottage was saved.

But it made me think about all the historic queer spaces that haven’t been saved? The homes, the community centres, the pubs and clubs that were important parts of queer life that were vacated or demolished and have disappeared from official histories as a result. What happened to all the gay clubs in London’s Earl’s Court? Or Quentin Crisp’s dirty bedsit in Chelsea? Or Libertas bookshop in York?

I want to know how we do the history of spaces like these and if it’s possible to access the feel of a place. So, as an experiment, I made an audio trail of my adopted city of Cambridge focusing on its queer spaces. The result, called "A Great Recorded History", is an immersive cultural history that uses interviews with older LGBTQ people and excerpts from queer literature. As you walk through Cambridge’s streets listening to stories from the past, layers of history are peeled away: that shop was once a thriving queer bar, this was where the Gay Society held its meetings… Work like this helps us to preserve a trace, a mood, a feeling of queer spaces that are just as important as Jarman’s Prospect Cottage.

Diarmuid Hester is one of the ten 2020 New Generation Thinkers on the scheme run by �鶹������ҳ��� Radio 3 and the AHRC to turn academic research into radio programmes.

Listen to Diarmuid Hester on Free Thinking.

Listen to Words and Music – Derek Jarman's Garden.

-

![]()

Free Thinking

Diarmuid Hester talks about the saving of Derek Jarman’s house and garden.

-

![]()

Words and Music – Derek Jarman's garden

Tilda Swinton and Samuel Barnett with readings from and inspired by the film-maker's work.

-

![]()

Free Thinking – Queer histories

What's the value of assessing whether historical figures were trans or gay?

-

![]()

The Film Programme

For Radio 4, Antonia Quirke and Larushka Ivan-Zadeh embark on a pilgrimage to Dungeness on teh 25th anniversary of Jarman's death.