Kwame Kwei-Armah: Nine things we learned from his This Cultural Life interview

On Radio 4's This Cultural Life, interviewer John Wilson speaks to Kwame Kwei-Armah, Artistic Director of The Young Vic theatre. Kwei-Armah’s career has seen him transform from musician, to Casualty star, to Olivier-nominated playwright, to his current position at the head of one of the most creative theatres in the country.

Here are nine things we learned.

1. The TV show Roots changed Kwame's life

Kwei-Armah grew up in West London, the son of parents who had emigrated from Grenada. He grew up rarely seeing black faces on television. Watching the TV series Roots, about an African man who is abducted from his village and sold into slavery in the US, changed him forever. “It was almost a near-religious experience,” he says. It gave him an understanding that he was connected to all other black people. “We hadn’t really been taught, or allowed to believe, that we had come from one source. Roots contradicted that. It said, ‘Just so you know, if you’re a black man, you’re an African’. In a way, seeing our history, through the lens of enslavement, but through the lens of humanity, even though enslaved, changed my world view.”

2. He changed his name after tracing his family tree

Watching Roots made Kwei-Armah look more into his own roots. He told his mother, at the age of 12, “I’m going to trace our ancestry and reclaim my African name.” Kwei-Armah was named Ian at birth. As he approached adulthood, he began tracing the family tree. “I traced our tree back to the slave fort that we came from in Ghana,” he says. “Then I took an ancestral name and changed from what was then Ian Roberts to what is now Kwame Kwei-Armah. And I’ve been Kwame for longer than I was Ian.”

3. He wishes he’d thought of Billy Elliot

Kwei-Armah was a performer from a young age. He realised he had talent as a singer and dancer by the age of seven. He went to stage school, which he adored. “I loved it. I loved the expression of it,” he says. “Years later, I saw Billy Elliot and I was really pissed off that I hadn’t written it. I lived that life! I lived through the Southall riots and it was happening all around me… I should have had that idea!”

4. One play showed him it was possible for him to work in theatre

An awakening happened when he saw August Wilson’s play Joe Turner’s Come And Gone, about a man who was enslaved and, now free, is on a journey to find his wife. “That was the moment I dedicated my life to theatre,” he says. “[Turner] was the first person to show me that you could have success and not compromise your cultural integrity… Hitherto, there was a kind of orthodoxy that the white cultural world wouldn’t accept you speaking your true self. Our black self had to be whispered in corners… He was speaking the words we whispered.” It was at that moment that he decided to write.

"It's the difference between pornography and live sex"

Kwame Kwei-Armah on the difference between TV and theatre.

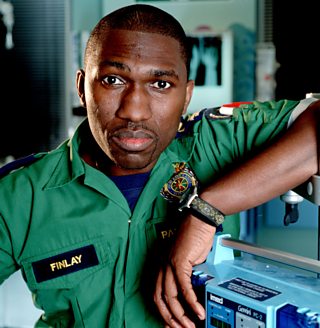

5. A crime inspired his breakthrough hit

Kwei-Armah had a very successful career as an actor. His most famous role was as Finlay Newton in Casualty, whom he played for five years. He always knew acting wouldn’t be for him long-term. “I knew I was frustrated at being an actor,” he says. He wrote his first play in 1998, the year before he started on Casualty, but it was his fifth play, 2003’s Elmina’s Kitchen, that set his career on a new path. It tells of a restaurant owner trying to keep his son from pursuing a criminal life. He began writing it after witnessing a crime. “Back then, guns on the streets of London and in the black community were relatively rare… Then there’d been an explosion of that kind of activity, which was shocking to me,” he says. One night, he was on a bus home when he saw a “BMW wrapped around a tree,” which he learned was being driven by two young black men who’d been shot, in a “Black-on-black crime.” It really distressed him. “I didn’t know what to do. Art is my only weapon, so I went home and started writing the first scenes of Elmina’s Kitchen that night.” The play won Kwei-Armah an Evening Standard Award, and later a BAFTA nomination for the television adaptation.

6. He abandoned his music dreams at 25

Before he became an actor, Kwei-Armah wanted to be a singer. He thought he “was going to be the kind of singer-songwriter that would emulate the Stevie Wonders of this world, who put depth into their lyrics.” He signed deals with record companies, including Sony, but by the age of 25 he realised it wasn’t working. “All my life I’d dreamt this was me and it evidently wasn’t.” He woke up one day and called his musician friends to give away his music equipment. “I said, ‘Yo, who wants to take my equipment? I’m not selling it, just who wants it?” He gave away a keyboard, a Korg M1, with a twisted key and his name scratched underneath. Many years later, he was doing a workshop in Senegal, when he spotted a keyboard with a key twisted like his. “I lift it, and it was my keyboard! My keyboard, from 20-odd years ago had found its way to a workshop in Senegal.” He doesn’t know exactly how, other than it had exchanged hands several times, but “I took it as [a sign] that I was where I’m supposed to be.”

7. His son has realised his father’s musical ambitions

Kwei-Armah is fully at peace with the fact his music plans didn’t work out, but he’s thrilled his son has had more success. “My eldest son is a producer called KZ,” he says. “He got his first platinum disc a few days ago, which he kindly brought to my house and said, ‘Dad, I thought you’d want to put this on your wall’. That feeling is a beautiful feeling. It wasn’t for me, but it was for him. I have no regrets.” Besides, the two have the same name. “It says it’s awarded to Kwame ‘KZ’ Armah. I’m just going to put a bit of black tape over the KZ.”

8. He thought he’d make 12 Years A Slave

When Kwei-Armah went to see Steve McQueen’s Oscar-winner 12 Years A Slave he was not only awed but professionally heartbroken. “I always thought I was put in the world of art to make a really big slave epic. That’s where I thought I was heading,” he says. After seeing McQueen’s film, “I came out of the cinema and went, ‘Oh no, he’s done it. Steve’s done it, and he’s done it beautifully. What else is there to do?’” He went into an existential spiral, because he didn’t know what his purpose was any more. The feeling lasted several years. “It had that profound an effect on me.”

9. He thinks TV and film are to theatre as pornography is to sex

Thankfully, the existential slump ended and Kwei-Armah has been hugely successful. He’s been the Artistic Director of The Young Vic since 2018 and says he still has a lot of work to do. Part of that is trying to tempt a young generation to come to theatre, instead of only consuming entertainment on screen. “They’re not lying when they say entertainment has never been so accessible,” he says, “but theatre is different. Theatre is life. Dare I say… it’s the difference between pornography and live sex. Nobody’s going to tell you that pornography is going to replace [sex].” And you probably won’t hear a better argument for live theatre than that.

More from �鶹������ҳ��� Radio 4

-

![]()

This Cultural Life: Kwame Kwei-Armah

Playwright and theatre director Kwame Kwei-Armah reveals his cultural turning points.

-

![]()

Screenshot

Ellen E Jones and Mark Kermode guide us through the expanding universe of the moving image

-

![]()

Male Order

Aleks Krotoski investigates sperm donors and the unofficial online fertility market.

-

![]()

Think With Pinker

Professor Steven Pinker’s guide to thinking better