Risky Business

Peter Evans examines current theories about risk-taking which are helping us to understand the origin and design of this essential yet puzzling universal trait.

Risk has played a key role in psychological research throughout the last century. Psychoanalysis defined habitual risk-takers as products of a 'deceased' mind since taking risks is all about overcoming, or ignoring, fears.

Since it was deemed irrational to ignore fear, psychoanalysis took a very dim views of those who deliberately put themselves into dangerous situations when there was no obvious advantage (such as self-protection). Mountaineers and gentlemen explorers were considered pathological.

In evolutionary terms, risk-taking could be said to have arisen, in humans at least, as a response to the harsh environment - an ice age for instance. Species that took risks in hard times, survived to propagate. More recently, risk has been associated with reproductive strategies - the peacock's tail and so on, where an animal trades speed or agility for some sign of sexual fitness. It was thought for a long time than humans were the only creatures capable of acting irrationally - But research has shown that animals act irrationally as well.

But risk isn't just one thing - and the picture isn't simple. But in social terms, there's evidence from studies to suggest that risk-takers are considered more sexually attractive, have more financial success, more friends and better careers. What's exciting researchers now however is the ability to study the link back from behaviour to personality to brain biology.

When talking about risk, psychologists refer to personality types which can vary in relation to a complex behaviour like risk. But the most common term in use is sensation-seeking, an defined personality trait. The father of sensation seeking is Marvin Zuckerman, still refining his theories about the biological basis of personality, half a century after he started.

Sensation seekers appear to be especially venturesome and inquisitive, eager to have new and exciting experiences even if they did contain a degree of social or physical risk.

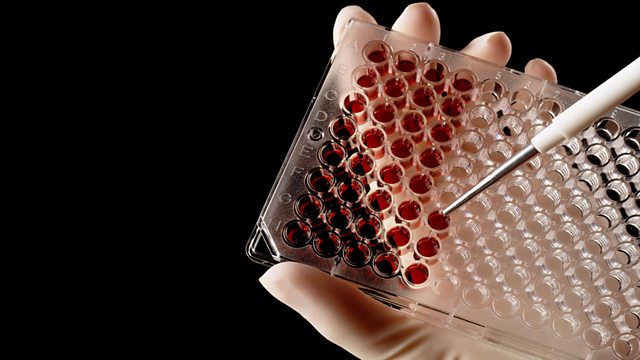

What's particularly exciting for Zuckerman and other researchers is evidence showing that a single gene - part of the dopamine system in the brain that mitigates rewards such as the feeling of pleasure - might be responsible for risk-taking behaviour. And what's more this gene might be overactive in people particularly prone to taking extreme repeated risks.

Not only do these initial findings point to explanations for extreme behaviour such as drug addiction or sexual promiscuity, it also goes a way to explain much more normal risk-taking behaviour that exists in all of us to a greater or less degree, helping us to understand the origin and design of these essential yet puzzling universal traits.

Last on

Broadcast

- Wed 20 Apr 2005 21:00麻豆官网首页入口 Radio 4

Podcast

-

![]()

Frontiers

Programme exploring new ideas in science and meeting the researchers responsible