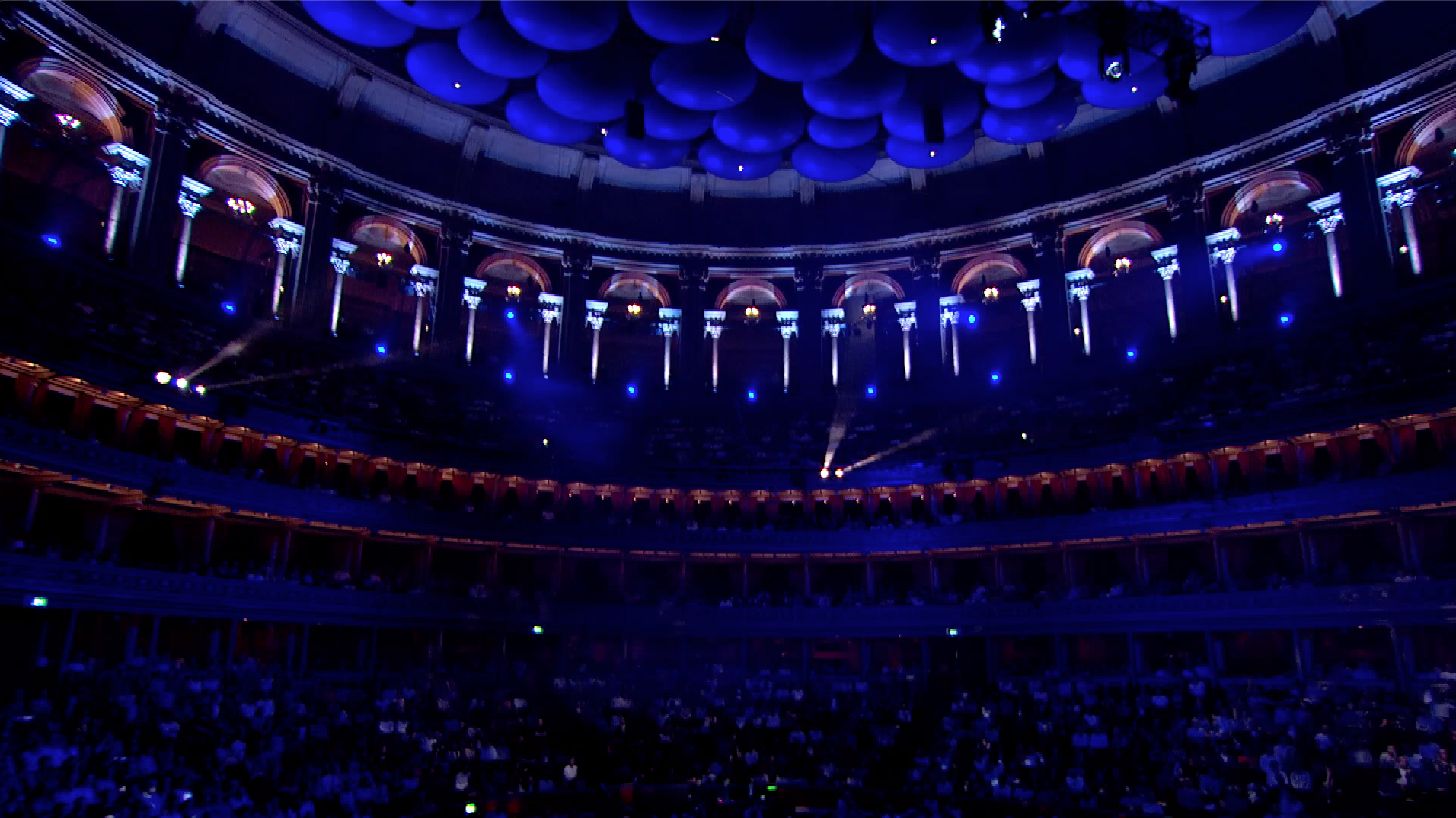

Beethoven from Memory

Thursday 10 September, 7.30pm–c9.00pm

Richard Ayres

No. 52 (Three pieces about Ludwig van Beethoven: dreaming, hearing loss, and saying goodbye) c20’

麻豆官网首页入口 co-commission: world premiere

(pre-recorded earlier today)

Tom Service and Nicholas Collon introduce Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 c17’

(script by Jane Mitchell, Nicholas Collon and Tom Service)

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 7 in A major 36’

(performed and conducted from memory)

Tom Service presenter

Paapa Essiedu voiceover (Beethoven)

Aurora Orchestra

Nicholas Collon conductor

This concert is broadcast live by 麻豆官网首页入口 Radio 3 and on 麻豆官网首页入口 Four at 8.00pm. You can listen to any of the 2020 Proms concerts on 麻豆官网首页入口 Sounds or watch on 麻豆官网首页入口 iPlayer until Monday 12 October.

Welcome to tonight’s Prom

Beethoven’s hearing loss plunged him into isolation and despair, so it’s hard to believe he was capable of producing a symphony such as his Seventh, which pulses with restless energy – and which the Aurora Orchestra tonight plays from memory. It’s a work with a special place in Proms history, too, being the last piece Proms founder-conductor Henry Wood directed before his death in 1944.

British composer Richard Ayres opens the concert with a deeply personal new work inspired both by Beethoven’s journey into deafness and his own experience of hearing loss, a vivid soundscape in which clarity gradually gives way to confusion.

In between these two works, Radio 3’s Tom Service and Aurora Orchestra Principal Conductor Nicholas Collon guide us through the programme with their customary lively and expert introductions.

Welcome to tonight’s Prom

Beethoven’s hearing loss plunged him into isolation and despair, so it’s hard to believe he was capable of producing a symphony such as his Seventh, which pulses with restless energy – and which the Aurora Orchestra tonight plays from memory. It’s a work with a special place in Proms history, too, being the last piece Proms founder-conductor Henry Wood directed before his death in 1944.

British composer Richard Ayres opens the concert with a deeply personal new work inspired both by Beethoven’s journey into deafness and his own experience of hearing loss, a vivid soundscape in which clarity gradually gives way to confusion.

In between these two works, Radio 3’s Tom Service and Aurora Orchestra Principal Conductor Nicholas Collon guide us through the programme with their customary lively and expert introductions.

Richard Ayres (born 1965)

No. 52 (Three pieces about Ludwig van Beethoven: dreaming, hearing loss, and saying goodbye)

麻豆官网首页入口 co-commission: world premiere

1 ♩ = 66

2 ♩ = 96

3 ♩ = 120

Although the subject of this piece is Beethoven’s progressive deafness and its effect upon him, writing it was also an opportunity for me to confront my own hearing loss. This is something that, until recently, I had been trying to ignore – despite its growing influence on how I live and my ability to socialise. In writing the piece, I expected to come face to face with these unavoidable truths and, if I was lucky and open to it, to reach some catharsis. Ultimately, however, I believe music should somehow transcend the person who wrote it: we shouldn’t be thinking of the composer, or the compositional process, when we are listening. So really No. 52 is not about me, or even Beethoven, but what the listener experiences.

Sound all around: I Hear Music in the Air, 2010, by Patricia Brintle (Bridgeman Images)

I Hear Music in the Air, 2010, by Patricia Brintle (Bridgeman Images)

The piece is arranged in three movements, each of which progresses from ‘audible’ to ‘inaudible’ via a method of distortion or obfuscation. In the first, a solo cello melody is gradually clouded by tinnitus-like, foggy strings. In the second, a piano – accompanied by the orchestra – is warped by the sound of a sampler keyboard. The final movement consists of four short pieces, each followed by the same music played through a record player. In those moments where some historical reference is required, I have deliberately written music that ‘looks a bit like Beethoven’. However, I have only quoted him directly once – in one bar of the solo viola part (in reference to a viola joke).

My relationship with Beethoven has changed dramatically as a result of writing this piece. I value him even more as a human being and a musical thinker. He seems to have lived bigger and more unrestrained by trivialities and difficulties than I could ever manage. Now I see what it is to live an intense, full life – even if I fall short myself.

Programme note © Richard Ayres

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92

(1811–12)

1 Poco sostenuto – Vivace

2 Allegretto

3 Presto – Assai meno presto – Presto –

______Assai meno presto – Presto

4 Allegro con brio

Wagner was only partly right when he called Beethoven’s Seventh ‘the apotheosis of the dance’. It’s even more fundamental than that. Rhythm really is it: the Seventh thrills with Beethoven’s obsessive focus on what he can make from just a few rhythmic cells, which he turns into structural building blocks with maniacal relentlessness.

Rhythm is inescapably the point of the main part of the first movement, whose dotted-rhythm Morse code is drummed out in nearly every bar, just as it’s drilled into our listening consciousness; rhythm is the catalyst for the ever-intensifying machine for mourning of the second movement; the third-movement scherzo is a vertiginous symphonic catapult, a challenge for us to keep up with the pace; and the finale puts a folk tune on rhythmic steroids, creating a churning centripetal force that sucks in the limits of the musical universe along with all of us listening and everyone playing.

The Seventh thrills with Beethoven’s obsessive focus on what he can make from just a few rhythmic cells, which he turns into structural building blocks with maniacal relentlessness.

But the Seventh does even more than that. This isn’t a piece about revolutionary ideas or heroes, it’s not a spiritual journey from darkness to light, it’s not about humanity’s relationship with nature, and it’s not about a composer showing how he can break through the conventions of previous generations. He’d done all of that – and more – in his previous six symphonies. He addresses the Seventh, not to our brains, but to our bodies. It is a sensory overload that pummels and pounds its way into all of the frequency-receiving parts of our anatomy: not only our ears, but our stomachs, our loins, our limbs, our feet, all of the parts of us that are made to move with and be moved by music.

The Seventh is the symphony as pure visceral experience, a piece that explodes fiercely and violently out of the bounds of the concert hall and into all the vibrating, resonating places of our bodies. We’ll explore how it gets inside the meta-body of the orchestra in our introduction to the symphony: an upbeat not only to a dance, but to an earthy apotheosis of symphonic grooving!

Programme note © Tom Service Tom Service presents ‘The Listening Service’, ‘Music Matters’ and other programmes for 麻豆官网首页入口 Radio 3, and has also presented on 麻豆官网首页入口 TV. A regular writer for ‘The Guardian’ since 1999, he is also the author of the books ‘Music as Alchemy’ and ‘Thomas Adès: Full of Noises’.

Biographies

Nicholas Collon conductor

Nicholas Collon (Jim Hinson)

Nicholas Collon (Jim Hinson)

British conductor Nicholas Collon is Founder and Principal Conductor of the Aurora Orchestra, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Gürzenich Orchestra, Cologne. He is also Chief Conductor and Artistic Advisor of the Residentie Orkest in The Hague until next year, when he becomes Chief Conductor of the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra.

Under his direction, the Aurora Orchestra has won recognition for its eclectic programming and its performances of complete symphonies from memory. It is Associate Orchestra at London’s Southbank Centre and appears each year at the 麻豆官网首页入口 Proms.

Nicholas Collon has also worked with orchestras such as the Danish National Symphony Orchestra, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre National de France, Oslo and Toronto Philharmonic orchestras and many of the leading British orchestras, including the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Hallé, London Philharmonic Orchestra and Philharmonia Orchestra.

His opera engagements have taken him to Cologne Opera, English National Opera, the Glyndebourne Tour and Welsh National Opera, and he has conducted over 200 new works.

He has made recordings with the Aurora Orchestra and acclaimed discs with the Hallé and Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra.

Tom Service presenter

Tom Service (麻豆官网首页入口)

Tom Service (麻豆官网首页入口)

Born in Glasgow, Tom Service graduated from York University and studied the music of American composer John Zorn for his PhD at the University of Southampton.

He began presenting Radio 3’s Hear and Now in 2001 and now regularly presents Music Matters, the station’s flagship classical music magazine programme, and the New Music Show. He also writes and presents The Listening Service, which has run for more than 120 episodes.

As well as fronting many Proms on 麻豆官网首页入口 radio and television, he has presented a number of 麻豆官网首页入口 TV documentaries, including a six-part series of 20th-Century Classics at the Proms, The Joy of Mozart and The Joy of Rachmaninoff – and three programmes, on Handel’s Messiah, Verdi’s La traviata and Shostakovich’s ‘Leningrad’ Symphony, with co-presenter Amanda Vickery.

He has written about music for The Guardian, of which he was Chief Classical Music Critic, and has given lectures at the universities of Cambridge, Oxford and York, and at Trinity College of Music in London. In 2018–19 he was Gresham Professor of Music at Gresham College, London.

Tom Service was Guest Artistic Director of the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival in 2005 and is the author of Music as Alchemy: Journeys with Great Conductors and their Orchestras and Full of Noises, interviews with the composer Thomas Adès.

Aurora Orchestra

Founded in 2005 under Principal Conductor Nicholas Collon, the Aurora Orchestra has quickly established a reputation as one of Europe’s leading chamber orchestras, garnering several major awards, including three Royal Philharmonic Society Music Awards, a German ECHO Klassik Award and a Classical:NEXT Innovation Award. Collaborating across across art-forms and musical genres, it has worked with a wide range of artists, from Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Dame Sarah Connolly and Patricia Kopatchinskaja to Björk, Wayne McGregor and Edmund de Waal.

A champion of new music, it has premiered works by many living composers, pioneered performances from memory and rethought the concert format with its Orchestral Theatre productions, which span diverse musical genres and art-forms.

Aurora is Resident Orchestra at London’s Kings Place and Associate Orchestra at the Southbank Centre. In addition to further residences in Bristol, Bury St Edmunds and Canterbury, the orchestra also appears internationally, including in Amsterdam, Cologne, Melbourne, Shanghai and Singapore.

Through an award-winning Creative Learning programme, Aurora regularly offers workshops and storytelling concerts for families, schools and young people. This year the orchestra launched ‘Aurora Play’, a free digital series showcasing the full range of its work.

First Violins

Alexandra Wood

Maia Cabeza

Katie Stillman

Alessandro Ruisi

Beatrix Lovejoy

Elizabeth Cooney

Peter Liang

Ian Watson

Second Violins

Eva Thorarinsdottir

Jonathan Stone

Agata Daraskaite

Tamara Elias

Cassandra Hamilton

Ronald Long

Violas

Nicholas Bootiman

Richard Waters

Asher Zaccardelli

Ruth Nelson

Cellos

Sébastien van Kuijk

Reinoud Ford

Ben Chappell

Peteris Sokolovskis

Double Basses

Ben Griffiths

Elena Hull

Marianne Schofield

Vera Pereira

Flutes

Jane Mitchell

Rebecca Larsen

Oboes

Thomas Barber

Michael O'Donnell

Clarinets

Timothy Orpen

Jonathan Parkin

Bassoons

Nina Ashton

Dominic Tyler

Horns

Steve Stirling

Hugh Sisley

Fabian van de Geest

Trumpets

Russell Gilmour

Imogen Hancock

Sam Kinrade

Trombone

Matthew Gee

Cimbasso

Sasha Koushk-Jalali

Timpani

Matthew Hardy

Percussion

Henry Baldwin

Keyboard

Iain Farrington

Sampler

Sally Pryce

The list of players was correct at the time of publication

We hope you enjoyed tonight’s performance

For full details of 麻豆官网首页入口 Proms 2020 concerts and broadcasts, visit bbc.co.uk/proms

Produced by 麻豆官网首页入口 Proms Publications