George Dixon was not having a good day. You could say he was a producer in a pickle.

He had to get two pieces of classical music on air for a live radio broadcast to schools. The presenter, Walford Davies, was already waxing lyrical, but there was no gramophone in his studio. This left George racing to find another studio where he could play the first disc into the show. In the nick of time, he found one. With the first record playing, he lowered himself into a chair with a sigh of relief. Right on top of the second disc.

Walford wasnтt fazed, saying live on air: тWell children, I did promise you an attractive piece by Brahms, but Mr Dixon has just sat on it.т

Such was the skin-of-the-teeth nature of schools broadcasting 100 years ago, the very beginnings of a story imprinted on many a UK childтs education. And as we take you back through a century of educational programmes, can we just check if you have your pencil and exercise book? We might ask you to take notes.

Calling all classrooms, this is the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк

Inform, educate, entertain. Those were the three main pillars for the British Broadcasting Company (ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк) set out by its first general manager, Sir John Reith, in 1922. With a whole third of that statement dedicated to enriching minds, it was perhaps no surprise that programmes for schools were an early part of that plan.

Arthur Burrows, the first ever Director of Programmes said in early 1923: тShortly we are commencing afternoon programmes in the provincesтІ in which case of course, the way is paved for a very important development in the use of wireless for instruction in the schools.т

The following year, it happened. An experimental lesson for a single school in Glasgow came first, then Friday, 4 April 1924 saw Walford Daviesт initial broadcast for schools, Music and School Life, transmit live at 3pm. This pioneering half-hour - where, presumably, nobody sat on his records - was the first of six weekly тtalksт, another of which was Climbing Mount Everest, presented by Lt Col Sir Francis Younghusband. Feedback from schools was generally positive, with the run extended further, and eventually a regular offering.

Differing school times around the country saw regional stations take up their own programmes. One example was a special - and impressively named - London Scholarsт Half Hour, going out between 4pm and 4.30pm on Fridays in early 1925, with one programme carrying the intriguing title, The Bigness of America (yes, really).

Into the war years

One of the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПктs aims was to provide experiences for students of all backgrounds that perhaps only the most privileged could previously enjoy, such as hearing from a professional speaker or musician. Right up until World War Two, schools programming was live. If any lessons needed to be repeated, scripts were simply re-used in a new broadcast. Teaching notes, available to schools, accompanied some programmes - a tradition that continued for decades.

From 1929, the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПктs educational content was guided by the Schools Broadcasting Council for the United Kingdom. They emphasised the need for children across the nations of the UK to have programming specific to their area and culture. It led to programming such as the Welsh language Ar Grwydr yng Nghymru (Wanderings in Wales), a radio series for older primary children in Wales, which aired from the 1940s into the 1970s. Discovering England was broadcast to rural schools in 1935.

Much later, the incredibly successful One Potato Two Potato brought musical accompaniment to lessons about life in Northern Ireland for primary pupils living there. Scotland This Century was another more recent radio series, focusing on history - but we're getting a little ahead of ourselves with the timeline here.

In the summer of 1940, the early days of war, a daily news service for schools began to reassure youngsters about anything mentioned in the bulletins for adults which may worry them. It even continued after the conflict ended in 1945, as did the radio services for schools. But minds were already turning to another way to bring lessons into the nationтs classrooms. This time, with pictures.

And now we can show you that equation

Almost as soon as the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПктs television service began in 1936, the potential for educational TV was explored.

Paperwork from 1939 records discussions on the idea, when it was thought scheduling issues made it impossible for programmes to coincide with school hours. As television resumed after the war, the idea was explored again, with a ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк engineer commenting in 1947 that the screen size at the time (approximately 10 inches - or 25cm) would make it impossible for an entire classroom to pick out details on any graphs and tables shown.

With various experiments in-between, it was 1957 when the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПктs regular Schools Television Service began, broadcast from Studio H in Londonтs Lime Grove Studios (the same complex where Doctor Who would be born six years later).

The launch earned a full-page feature in that weekтs Radio Times. Enid Love, assistant head of schools programming, proudly introduced the multi-purpose set with its magnetic map of the world, back projection screen and the possibility of staging тsimpleт dramatic productions.

Love wrote: тOur brief from the Schools Broadcasting Council is to explore the educational possibilities of television, not to use television as a means of transmitting outstandingly good lessons or lectures.т

Can you see me from the back of the class?

At 2pm on Tuesday 24 September, a five minute The image, usually in the form of a graphic, that aired before TV programmes in the early days of broadcasting. This enabled viewers to tune their sets for the clearest image possible. was followed by For the Schools: Living in the Commonwealth, the first ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк Schools programme in vision. Introduced by Bernard Braden, it took a closer look at life in British Columbia, Canada.

As the weeks progressed, there was a live broadcast from the Metropolitan Police Driving School in a programme focused on careers. Presenter Christopher Chataway hosted a current affairs show focused on the Middle East and another programme looked at how Science Helps the Doctor.

Television for schools, later known as ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк Schools and Colleges, went on to become part of the fabric of many a UK childтs school-life. They reflected different aspects of life across the country. For example, the long-running Welsh language series Ffenestri (Windows) was made for primary schools from the 1970s into the 1990s. Around Scotland was another series with a lengthy run, the geography-based programme beginning in 1959. Ulster in Focus began in 1967, featuring various subjects for primary and secondary pupils in Northern Ireland.

Chips werenтt just for school dinners

The possibilities that computers could bring to the classroom were recognised by the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк as the 1980s got under way. The ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк Micro, with its beige casing and disco orange function keys, were a regular sight in UK classrooms, along with educational games such as the puzzle-based Grannyтs Garden - watch out for the witch!

When the т90s arrived, increased internet usage came with it. On 18 January 1998, Bitesize (or GCSE Bitesize as it was first known) was launched, offering revision help on seven core subjects at a time when just under 10% of UK homes had internet access. Over 25 years later, thatтs become more than 35 subjects at Primary and Secondary level. The spirit of Granny's Garden also lives on in educational games such as Karate Cats and Guardians: Defenders of Mathematica.

Learning in a time of lockdown

The most significant moment in Bitesizeтs history (perhaps even the history of the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПктs educational provision) came in early 2020. When the country went into lockdown to help prevent the spread of Covid-19, something had to be done to ensure school pupils could carry on their education at home.

Helen Foulkes, head of the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк's Education department, remembers Monday 16 March as an ordinary day that quickly developed into something far, far more challenging: тWe had an initial meeting about how Childrenтs and Education could support children if there was a lockdown, though it really felt like contingency planning. Fast forward 24 hours and it was happening.т

Less than five weeks later, on 20 April, the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПктs Education Service was launched. A massive 197 hours of the brand new Bitesize Daily programme were made from scratch over 14 weeks of the summer term to support parents, teachers and pupils, with more than 2,000 lessons curated from Bitesizeтs existing online content.

Helen continued: тTo create almost 200 hours of programmes from scratch with only three weeks pre-production would be a challenge in normal times but the Bitesize Daily team had to deliver this from conception to broadcast under social distancing rules, with Joe McCulloch, one of the executive producers, walking around with a two-metre ruler to stress the point!т

Editing was completed the night before transmission, lessons quality assessed by education professionals and, within a month, teachers were able to get 48-hour notice on which subjects were coming up for broadcast. Such was its success, Bitesize Daily continued after pupils began their return to school, and Helen holds it up as a solid example of how the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк has supported young learners in its first century.

тEducating people is at the core of the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк,т she said. тFrom the outstanding work of the Natural History Unit to our amazing News coverage.

тI think we should offer our audience a range of ways to learn with the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк. From ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк Bitesize online content that students can interact with and learn at their own pace, to educational programmes such as Bitesize Daily and Live Lessons which are available on iPlayer and on CТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк.т

You can put your pencils and exercise books away now. There wonтt be a test today.

After a century of hard work from students everywhere, please - take some time out to play instead. Youтve earned it.

We're marking 100 years of ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк Education with a special Behind the Scenes at the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк Literacy Live Lesson for primary schools on Monday 22 April. You can also get a tinge of nostalgia with our from the 1920s to today.

This article was first published in October 2022 and updated in April 2024.

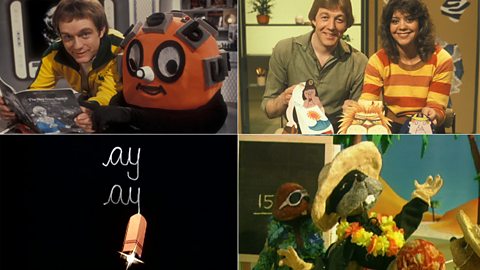

100 years of ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк Education: A nostalgic trip through the decades

A look back on a century of ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк Education content - from the wireless to Play Away to Bitesize Daily

Quiz: Which of these famous faces became teachers for a day?

The well-known names that have delivered lessons to the nation on the ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк

Three centenarians remember their school days

Looking back at classroom life when ТщЖЙЙйЭјЪзвГШыПк Education was just beginning