Paul: A Misunderstood Disciple

Dr Helen K Bond is a Senior Lecturer in the New Testament and Director of the Centre for Christian Origins at the University of Edinburgh's School of Divinity.

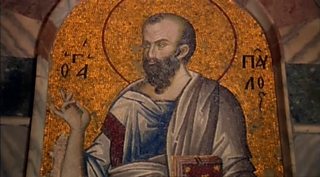

The apostle Paul often gets a bad press. While many non-Christians regard Jesus and his values in high respect, the same isn’t true for Paul. More often than not he’s seen as the epitome of all that’s unattractive about ‘organised religion’ – narrow minded, bigoted, and set in his ways. But all of this couldn’t be further from the truth, and a documentary, in which David Suchet travels In the footsteps of St Paul, aims to bring early Christianity’s most energetic and creative thinker to life.

The most important thing to remember about Paul was that he wasn’t writing timeless theological tracts, but letters. Back in the 50s of the first century, there were no creeds or gospels (it would be twenty years before Mark picked up his quill). The message of Jesus had been delivered to rural peasants but now, thanks to the efforts of Paul and men like him, was spreading rapidly in the cities of the eastern Roman Empire. Working out what it meant to live a Christian life in these radically different environments was no easy matter. And it’s the questions and concerns of these early Christian groups that Paul tried to address in his letters.

Central to Paul’s thought was the conviction that, through the death and resurrection of Christ, God had inaugurated a new way for humans to be saved. But beyond this, his letters show an ability to adapt and to respond to the pagan world around him. At the heart of his teaching was a concern for the feelings of others, an almost fatherly pride in his Christian converts, and a desperate desire to protect them. When he advised the Corinthian Christians not to marry, it wasn’t because of any kind of misplaced asceticism, but simply because he believed that the end of the world would come soon and he hoped to save them from the added burden of worry about their family.

Of course, Paul was intolerant towards people who disagreed with him, but he was also capable of changing his mind. His radical change of heart on the Damascus Road must go down as one of the most dramatic u-turns in history. What is striking here, though, is that Paul didn’t need to have any further public engagement with the new faith; he could simply have taken himself away and kept a low profile. In fact, this is what he did do for several years, apparently working out the implications of his new-found faith. But the contemplative life held few attractions for a man of Paul’s vigour, and soon he was back, this time as one of Christianity’s foremost apostles. We’re so used to the story of Paul that we often don’t appreciate just how difficult this must have been for him. With the best will in the world, those early Christian communities must have been deeply suspicious of him, and those first few years as a missionary must have been friendless and uncertain times.

Perhaps the area where Paul has been most maligned is in his attitude towards women. A particularly illuminating passage is Romans 16. This is the very last section of a letter written to the church in Rome, a church Paul didn’t found and wasn’t too familiar with. In this final section, he lists all the people he knows at Rome, and asks that they vouch for him. What is striking is that a third of all the people are women, and they are referred to by Paul as deacons, apostles, and leaders of house churches. But most importantly of all, the letter to Rome – one of the most important letters that Paul would ever write – was sent to the church by the hand of a woman, Phoebe. She might well be the one to read it out, and would certainly be expected to explain anything that wasn’t clear. If we ever needed any reassurance regarding Paul’s high regard for women’s abilities, this is surely it!

As the first century wore on, however, the situation of early Christians changed. They gained a more secure footing in the cities of the east, the earliest generations of Christians had now died, and the intense expectation that the end of the world was imminent began to fade. So great was Paul’s legacy, that his followers began to write letters in his name, outlining what the great apostle would have said had he been there. Their concern now was to fit in with Roman society, to restrict the role of women, and to present a well-ordered and respectable faith to the world. Scholars are generally agreed that letters such as Ephesians, the Pastorals (1 & 2 Timothy, Titus), and possibly Colossians and 2 Thessalonians weren’t written by Paul at all, but by his late first century followers. Its easy for us to be a little shocked by this – it smacks of fraudulence and forgery. But what those disciples had learnt from Paul was that, as long as the core beliefs remained intact, the Christian gospel has to adapt and to accommodate itself to the surrounding world.

I sometimes wonder what Paul might think if he knew we were poring over his letters two thousand years later. I think he’d be genuinely surprised. Not only because he never expected to be writing for posterity, but because it shows such impoverishment in our own times. I’m not advocating a free-for-all, or that we abandon Paul’s literary legacy – his work still has much to teach us. But for Paul, new challenges and situations didn’t involve a retreat to the past, but were things to be faced head-on, with energy, creativity, and an openness to the Spirit. Perhaps Paul’s real legacy isn’t his letters at all, but his advocacy of an ongoing dialogue between the Christian community and the outside world.

Clips

-

![]()

David Suchet retraces the controversial figures footsteps around the ancient Roman world.

-

![]()

As St Paul brought his message to Europe he had to challenge Pagan society values.