Fish in the trees

By Emma-Louise Phillips, Assistant Producer

In order to film one of Asia’s most surprising fish we spent a month camping in an empty scientific research station on a deserted Indonesian island.

There was no running water, no internet, no electricity...

Getting to Ujung Kulon - a national park on the southwestern tip of Java, took several days' travel by air and road, and one hair-raising journey across stormy seas in a traditional fishing boat known as a jukung.

Exhausted, drenched, but exhilarated, we finally arrived at our location - a sandy, palm-fringed island filled with tangles of pristine mangrove forests, crocodile-infested lagoons and screeching monkeys. There was no running water, no internet, no mains electricity, and no connection to the outside world at all. It would just be us and our funny little fish friends for the next month.

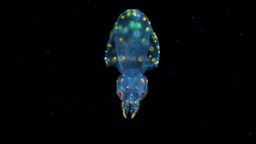

Dusky-gilled mudskippers are one of the smallest of the 32 known mudskipper species, but even at a mere four centimetres long, they are full to the brim with moxie.

...even at a mere four centimetres long, they are full to the brim with moxie.

Our team watched in awe as the mudskippers scaled trees, clambered over rocks, deftly evaded predators and enthusiastically pounced on worms. They defended their territories against all incursions, energetically pursued mating opportunities, and to my delight, seemed entirely indifferent to my presence. I grew to love the sight of them blinking up at me with their cartoonish eyes as they shimmied up my legs to gain a better view of their surroundings. I felt delightfully like Gulliver, surrounded by tiny, slippery Lilliputians.

To film this giddying array of behaviours we relied on a specialist macro probe lens, which enabled Bjorn Vaughn, our wonderful cameraman, to get right down to their eye level and see the environment as they see it. Watching the footage back each evening provided a glorious window into their world - what it is to be a fish in a forest.

Ben Harris was the second camera operator, and together we spent days and weeks amongst the trees looking for suitable places to film the mangroves.

The mangroves felt like another character in this story...

Our regular barefoot scrambles through the jungle, knee-deep in marine mud, with expensive camera kit held precariously aloft, were equal parts challenging and exciting. The mangroves felt like another character in this story, every bit as unlikely as the mudskippers themselves, and the quest to showcase their beauty and strangeness was our daily obsession.

Mangroves are not a single species, but a number of different types of tree that thrive in saltwater, and Indonesia has more of them than anywhere else on Earth. Their importance as an ecosystem is hard to overstate - not only do they protect coastal regions from erosion and storms, their submerged roots provide shelter for countless juvenile reef fish, rare and endangered types of coral and several threatened shark species. On top of this, they sequester four times more carbon dioxide than other tropical rainforests. They are some of the most vital ecosystems in the world, not just locally but for the whole planet.

Our crew had the privilege to be joined by one of the world's foremost experts in mudskipper behaviour, Dr Bambang Retnoaji. A man of senior years and immense experience, Bambang put us all to shame holding his video camera aloft on every boat trip, grinning wildly while the rest of us clung to the sides for dear life; a more affable, enthusiastic and adventurous companion you would struggle to find.

Perhaps the funniest quirk of all is the mudskippers aversion to water.

Long, fascinating afternoons were spent with Bambang watching the mudskippers excavate their subterranean dens, diligently removing mouthful after mouthful of wet sand in preparation for egg-laying.

The males of the species are especially devoted fathers and spend weeks caring for their eggs (somewhat unusually, the females leave shortly after laying the eggs and play no further part in their care). The egg chamber is about 30 centimetres below ground where it is nice and cool and safe from predators, but without ventilation, oxygen levels can drop dangerously low. To combat this problem, the fathers tirelessly carry mouthfuls of fresh air from the surface down to the chamber to prevent their precious eggs from suffocating. It’s a process that needs repeating all day, every day until the little ones are ready to hatch.

Perhaps the funniest quirk of all is the mudskippers’ aversion to water. They go to extraordinary lengths to bounce, hop and scuttle away from an incoming tide, and will avoid being submerged at any cost. Dusky gilled mudskippers have a remarkable form of locomotion that was only recently discovered - the ‘water hop’. Scientists already knew that they could waddle across the sand using their muscular pectoral fins, but it wasn’t until 2020 that a research team (Bambang, our scientist companion amongst them) discovered that they can bounce across water like living, breathing skimming stones - a behaviour we captured, we believe for the first time, for the series.

...these stranger-than-fiction fish and their forest felt like a privilege.

Whilst we spent long days filming in the mangrove forests, besotted with these strange amphibious fish, bands of local macaques were free to raid our camp, entering through the glassless windows to ransack our rooms and relieve us of our carefully hidden snacks. In the evenings, herds of deer would emerge from the forest to sit with us as we ate our evening meals. Despite the humidity, the storms, the occasional bouts of sickness, the mosquitoes and the marauding primates, it’s fair to say that filming these stranger-than-fiction fish and their forest felt like a privilege. Everything on this island seemed magically upside down; wild deer ran towards people, trees grew from the sea and the fish were afraid of water.

The fish that lives on land

Male mudskippers walk on land, climb trees, and battle to win a female鈥檚 affection.