Reef rivals: sharks on the hunt for Moorish idols

By Seth Daood, Researcher

How exactly do you film a high-speed underwater shark chase with state-of-the-art wildlife camera equipment? This was a question we did not entirely have an answer for when we arrived in the middle of the Pacific Ocean hoping to capture one of the rarest, and least-known, feeding frenzies in the natural world.

...they are met by huge hunting packs of sharks...

Moorish idol fish typically spawn in pairs, but in certain areas of the Western Pacific, if you are lucky, you can see huge numbers of them gathering on the reefs in what is believed to be a mass spawning event. This only happens once a year – at one of two sites, in either January, February or March. With the help of our incredibly experienced local team, headed by Mandy Etpison, we studied historic spawning records, and decided February would be the month with the best chance of success. Even so, it was a nerve-wracking wait – you can never quite tell how animals might respond to the moon, the tides, and the currents.

If everything went to plan, we would see fish numbers slowly building over a few days, before the idols dashed out from the safety of the reef and into the deep blue to spawn. Unfortunately for these fish, when they rush from the reef, they are met by huge hunting packs of sharks.

For something so small, the Moorish idols are very efficient swimmers. At their maximum speed, we had been told our boat would have to move at ten knots to keep up with them. The first challenge was working out how to get the camera attached to the side of the boat in the first place. We sourced a long piece of timber and after making sure it could hold the weight of three of our team, we ratchet-strapped it to the deck.

Our cameraman had been developing a retractable pole for use across the Asia series, which attached to the timber and hung over the side of the boat.

Suddenly, at 11:20 exactly, we saw splashes on the surface of the water, and all systems were go.

This pole could be lifted out of the sea to allow us to travel at faster speeds, and quickly lowered back into the water when we were close to the action and travelling more slowly. Our hope was that we wouldn’t break the camera, pole or timber as we chased the fish.

Six days before the event was predicted to start, it was time for a test drive. We managed to get the boat up to three knots before the camera and the timber started shaking – and this made everybody nervous.

We added a second plank of timber, and managed to reach just under five knots. A few extra ratchet straps and we were ready to go, or so we hoped. On the day the feeding frenzy had been predicted, we anxiously waited, our crew ready to spring into action. Suddenly, at 11:20 exactly, we saw splashes on the surface of the water, and all systems were go.

At once, our crew of five people had to be filming underwater, from the side of the boat, and from the sky simultaneously. Clad in a bright green helmet, a single thick glove, and goggles, I was working with the aerial team to launch our drone, follow it in the sky and relay its position to the boat skipper, and catch it when its battery needed changing. Each drone contained vital footage of this super-rare event, and catching it felt briefly like the most important thing I’d ever do. The thought of dropping it into the ocean made me feel nauseous – or perhaps that was the seasickness at work!

...it felt briefly like the most important thing I’d ever do.

As the frenzy continued, we were determined to film it from start to finish, following the idols for over an hour into the deep blue, as their numbers steadily, and sadly, diminished. From the initial shoal, hundreds strong, there were eventually barely enough to count on two hands. I never thought I would witness such a spectacle in my lifetime. I’ve spent years studying evolution and behaviour, but to be able to witness such a gruelling demonstration of survival of the fittest, made me fully appreciate every example I had read about in a textbook.

Returning to land, we were eager to share our footage with the local scientists and naturalists who had helped us. Being able to show leading experts footage of events they have not been able to witness directly, helps us to contribute to new scientific research. This is an aspect of wildlife film-making that’s sometimes overlooked, but it’s one of the things I am proudest of, coming out of this series.

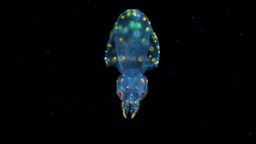

Moorish idol fish chased by huge school of sharks

Vast numbers of sharks pick off Moorish idol fish when they venture into open water.